“If the English can survive their food, they can survive anything.”

Tossing a penny for a pie

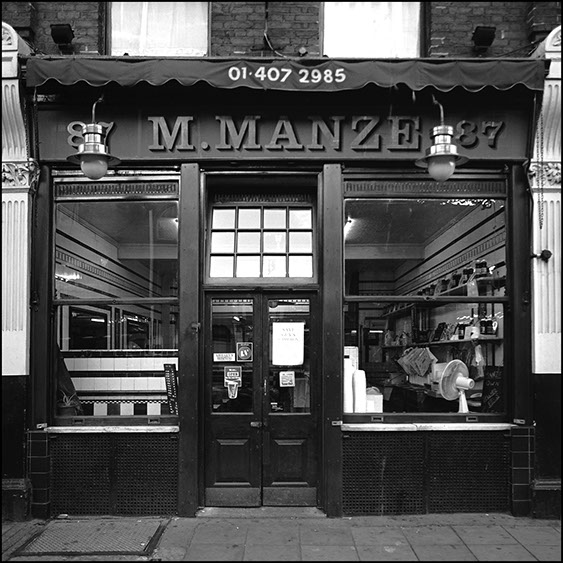

Predictably for a dish with such proud British lineage, there is some debate over the history of pie and mash, where it began and with whom, but it is generally conceded that M. Manze, the Manze’s branch in Tower Bridge is the oldest surviving pie and mash shop, having opened in 1892. The first shop on record was on Southwark’s Union Street, opened in 1844. These shops were descended from the travelling piemen that travelled London’s streets selling pea soup and hot eel pies, frequenting fairs and taverns as well as the industrial City’s engine rooms: the docks, the workshops and the markets. It was common to toss a penny for a pie - if the pieman won, he’d walk away with the penny and the customer with nothing, but if the customer won, they’d get the pie and keep the penny.

In Victorian London the prevailing westerly wind meant industrial air pollution predominantly affected the East and Southeast of the city. Industrialisation also meant a massive growth in the urban population, with people relocating from rural Britain as well as to escape famine in Ireland and persecution in Europe. Settling in the smoggy East of the city, these new working classes needed cheap, fast and plentiful food, many didn’t have the facilities to cook for themselves. Under these conditions, pies had long been a staple food, calorie dense but small and portable, protected from dirt and pollutants by its thick water crust pastry. In the new pie and mash shops, food could be ready in minutes, if not seconds and pretty soon there were queues down the street every day, with shops often selling out of pies.

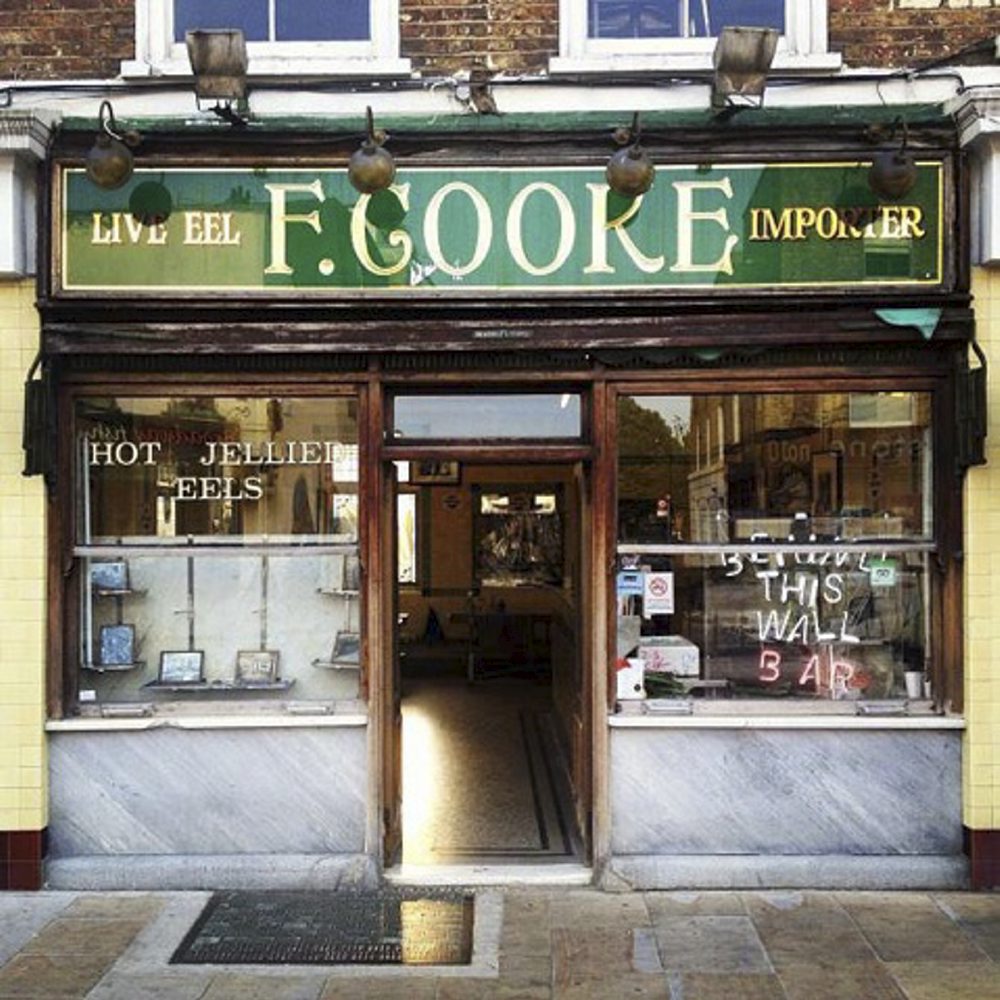

F. Cooke in Broadway market and M. Manze on Tower Bridge Road, then and now.

Although pretty soon the shops’ popularity meant they were popping up all over Southeast and the East End, there are two families that have long dominated the trade: The Manzes and the Cookes. Michele Manze was an Italian immigrant who came to London in 1878 aged 3. He and his family settled in Bermondsey as ice merchants. After a brief foray into the ice cream trade Michele Manze married the widowed daughter of Robert Cooke, the reported creator of the iconic pie, mash, liquor trio and all around pie-shop legend. It was a union that was to prove historic for British food, with Manze taking on Cooke’s Tower Bridge shop in 1902 and quickly expanding into the trade along with his brothers. By 1930 there were 14 establishments under the Manze name and while some are long gone today, the Southwark and Deptford branches remain in the hands of direct Manze descendents.

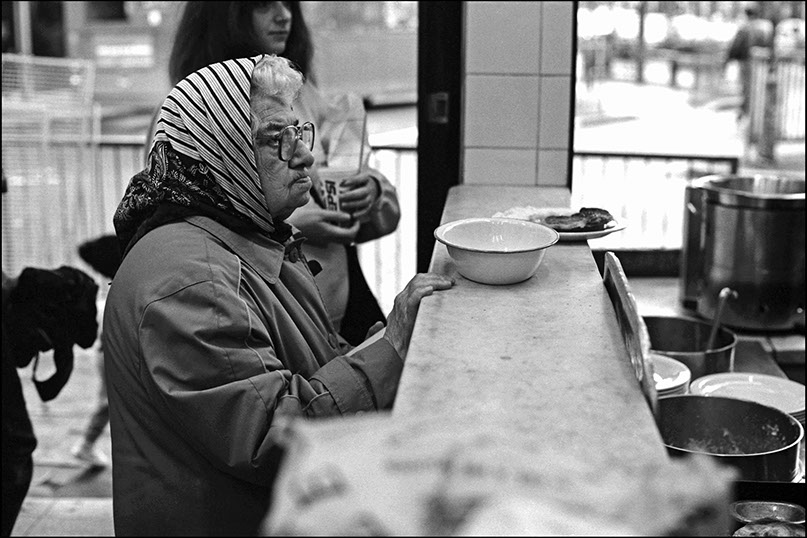

Photographs from the series 'Eels, Pie and Mash' by Chris Clunn

Like the rest of the old school crowd, The Manzes’ shops have been proudly serving up the same recipe for the 200-odd years that they have been in business (the only addition being a vegetarian version of their legendary pies), serving up to 300 meals a day. During World War II rationing sparked concern that the shops might have to close, an appeal was made to the Ministry of Food, persuading them to provide a quota that allowed the eateries to remain open (plus, potatoes were one of the few foods not rationed) and they proved crucial in supplementing people’s food rations, often staying open til midnight to accomodate customers. It was in this way that foods like pie and mash and fish and chips became more mainstream British food staples, making their way up the social ladder and onto the plates of the middle classes. It was during the war that the two Manze shops in Poplar were lost to air raids. The gradual closing of the London docks from the 60s to the 80s put huge pressure on the businesses to remain open, and eventually many had to close as their customers sought employment elsewhere.

“[Manze’s] illustrates a type of establishment, and a type of cuisine, that formed a staple of early 20th Century working-class life”

The surviving shops are revered as living pieces of British history - with both the Tower Bridge and Peckham outlets being awarded listed status and Blue Plaques. This was in spite of the Peckham branch being set alight in the riots of 1985, that coursed through London’s streets - from Brixton to Tottenham - following the murder of Cherry Groce by metropolitan police during a raid on her house in search for her son, Michael, wanted for gun crime. They remain recognised for their architectural and cultural significance for English heritage and a resurgence of interest in British culture and cuisine has meant that business is good. The traditionally tiled walls, mirrors and marble worktops and floors, fairly standard for their day and selected on account of being quick and easy to clean, now have a hallowed feeling of art deco authenticity (the sawdust that once covered the floors for spat out fish bones has, thankfully, been left to the past). And that’s not all that’s authentic: in the kitchen, everything is still done from scratch and with the utmost care, despite what the lightning fast hands might suggest.

There are conflicting reports as to how eels wriggled their way onto the menu. Highly nutritious, easily digested (and apparently aphrodisiacs), they had long been a working class staple, with some historical accounts claiming that this was on account of their being the only fish able to survive London’s polluted waters, which were reportedly ‘writhing’ with them. Elsewhere they are reported to have arrived on Dutch vessels making their way up the Thames, depositing them in droves at Billingsgate market, which then sold them on cheaply to the piemen and later the pie shops. Indeed, back in the day as well as picking up your plate of jellied eels, you would also pick up a few to take home - "all alive, every one’s got a bright eye and silver belly,” - the quality assurance of the day. Not for the faint hearted, the eels are still kept in water, alive (if a little dazed) until they are about to be cooked. With a single deft slice at the back of the fins (or ‘ears’) the eels are killed, gutted and cleaned before being sliced into chunks and into boiling water with a scoop of pimentos for around 7 minutes until tender. Naturally high in gelatine, back in the day the eels would have been left in some of the cooking water to cool and set on their own, today they’re given a bit of a helping hand with some powdered gelatine and refrigerated overnight. The ‘eel-water’ also forms the base of the famous liquor sauce that is the crucial accompaniment to pie and mash. Most shops have their own closely guarded recipe for the mysterious green sauce, usually including parsley, vinegar and wheat flour.

So take a trip back in time: settle into one of the shops’ dining booths, steeped in history, and tuck into the plate that has nourished British culture for centuries. And if you find yourself in Deptford, use your South London Club card for 10% off - on the Manzes!